During the 1940s and 50s, groundbreaking research hinted at the transformative capabilities of psychedelic drugs in enhancing mental well-being and treating chronic mental illnesses. Yet, it has been over 70 years and psychedelic-assisted therapies are still not approved in most countries. So what happened? And are we finally making progress?

Today, as attitudes shift and research gains momentum once again, we find ourselves on the cusp of a potential renaissance in psychedelic therapy.

A trip through time

Since Albert Hofmann accidentally dosed himself with LSD in the 1940s, thousands of scientific research papers were written on the transformative effects of psychedelic drugs. Whilst many of these studies were not done to the rigorous standards of today's research, they hinted at an extraordinary therapeutic potential across a wide range of mental health and psychiatric conditions.

What stood out about this type of drug was that, unlike others, a single treatment could cause a cascade of neurobiological changes. Psychedelics could open a door to fundamentally alter long-held beliefs and be used as an accompaniment to therapy. Quite different to the long-term monoamine-oxidase or serotonin reuptake inhibitors that reined in the fifty years that followed.

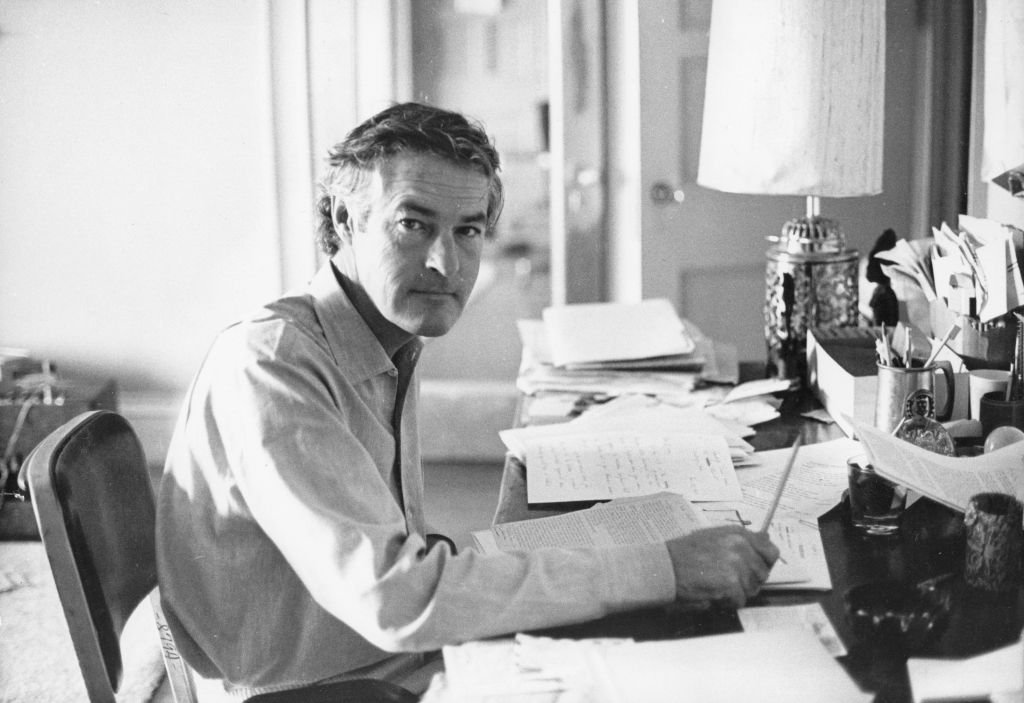

So transformative were the effects being reported that some researchers had little discipline for keeping psychedelics within the lab. In 1963, Harvard University famously fired two prominent psychologists, Dr Timothy Leary and Dr Richard Alpert, after they were caught promoting and using psychedelics with students. Both men would later become key figures of the psychedelic drug counterculture movement.

The 1960s need little introduction, but it perhaps speaks to the revolutionary power of these compounds that by the end of the decade, psychedelics had been outlawed from society completely, even from academic research. Thirty years of prohibition and stigmatisation would follow, and with that, any hope that psychedelics might contribute to the well-being of patients.

The science of psychedelic medicine

Whereas most treatments in psychiatry have a targeted application, psychedelics appear to show promise across an unusually broad range of therapeutic targets. The classic psychedelics (LSD, psilocybin, DMT, mescaline) all share a primary site of action - Serotonin 2a receptors (5-HT2ARs). It is the impact on this signalling pathway, often resulting in profound visual, emotional and cognitive changes, that could hold the keys to understanding this 'higher order' efficacy.

Some researchers speculate that it is these changes in perception, the lived experience of seeing things differently, that could be so therapeutic. In one afternoon of guided psilocybin treatment, patients can achieve a perspective that could otherwise take years of traditional talking therapy alone. When locked in a narrative about your past or future, which is so often the case with conditions such as anxiety and depression, being able to access an alternative perspective may be life-changing.

Others point to the inherent meaningful value of this perspective shift that can occur when psychedelics are taken under optimal supportive conditions. When participants of studies are asked 'how meaningful was the experience', on a lifetime scale, between 80% and 90% of participants describe the experience within the top 5 most meaningful experiences of their life - comparable to the birth of a first child.

The experience has several features or themes that are routinely measured by well-validated and widely used psychiatric surveys, and often directly opposed to key symptoms of psychiatric disorders such as depression:

A profound sense of unity and interconnectedness between all things

A sense that there is something sacred or reverent about the experience

Ineffability - the experience simply cannot be understood or communicated through language

Feelings of peace and joy – open-heartedness, awe, gratitude, recognition and appreciation of deep beauty

Transcendence of time and space - the past and future collapse in the present

The noetic sense - the feeling that there is something 'more real' about this experience - an intuitive belief that the experience is a source of objective truth about reality

While many questions remain about the biology and underlying science of psychedelics and how they relate to health, spirituality, morality and social behaviour, it seems clear that they have an important role to play in the future of mental health.

Despite their potential, psychedelics still face stigma

Since 1971, psychedelic substances have been labelled as among the most dangerous by the UN, who gave them Schedule I status in the UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances. This reputation has proven hard to shake. While the convention originally intended only to stop the recreational use of psychedelics, the UN declared that the therapeutic value of psychedelics was “limited”, which hampered academic research in the field. Combined with the US ‘war on drugs’, the promising therapeutic research took a steep nosedive away from the doctors’ office and into counterculture.

But now, a surge of new research indicates that the initial stance of the UN might not have been quite right.

In the last few years, we have witnessed a renaissance of psychedelic research, fuelled by a desire to find new and improved treatments for mental health care, as well as the hope that psychedelics may offer clues toward a working theory of consciousness.

In 2019, the Centre for Psychedelic Research at Imperial College London and the Centre for Psychedelic & Consciousness Research at Johns Hopkins became the first dedicated centres to investigate psychedelics. Many clinical trials exploring psychedelic-assisted therapy across a wide range of mental health conditions are currently ongoing around the world.

When will psychedelic-assisted therapy be readily available?

In January 2023, Oregon became the first US state to legalise the adult use of psilocybin under the supervision of a licenced guide, with Colorado residents recently voting to do the same. Legislation to legalise psilocybin has also been introduced in states including Connecticut, New Jersey, and California.

Following a series of successful phase 3 trials, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) are expected to file for US FDA approval of MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD in late 2023. MAPS Founder and executive director, Rick Doblin, believes the FDA could approve MDMA-assisted therapy as early as April or May of 2024. Australia began allowing psychiatrists to prescribe MDMA for post-traumatic stress disorders and psilocybin-based therapies for depression in 2023. Physicians in Switzerland, Canada and Israel are currently allowed to use psychedelics in strictly controlled circumstances.

In the EU, the UN convention was turned into regulation with the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, restricting the use of psychedelic compounds to research. However, there is increasing pressure to declassify them, as has already been done with cannabis.

Earlier this year, seven members of the European Parliament formed the Action Group for the Medical Use of Psychedelics, joining the European Psychedelic Access and Research Alliance in their mission to integrate psychedelic therapies into European mainstream health services. In 2019, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) approved psilocybin for a phase 3 study in treatment-resistant depression, and although it has not reached the market, earlier this year, they confirmed that there are currently 11 ongoing clinical trials for psilocybin (including for MDMA and LSD) in the EU.

The EMA has explicitly said that psychedelics are subject to the same evaluations as other treatments. However, none are yet approved and getting these treatments to patients may be far down the list of priorities of the EU.

Conclusion

Despite the potential, tearing down the blockades of the last 70 years and creating a positive environment for psychedelic-assisted therapy is not at the forefront of health policy goals.

Researchers, pharmaceutical companies, policymakers and regulators around the world will face a range of novel communications challenges in bringing these therapies to patients. We are passionate about supporting these efforts and will be working hard to stay on top of trends and changes in the space.

This article was co-written by James Cockerill, Vice President at Cherry USA and Ellen Moyse, Senior Consultant at Hanover.