Resilience is based on the people around you. They are the only people who will understand what you’re experiencing; they are the only people able to really appreciate what you’re feeling.

This yields a collective resilience based on shared experience that no one else can understand. And with this comes a sense of hope that you will come through this, that this is transitory, and that you have faith that the future must be better than the present, because nothing could be worse than what you’re experiencing right there.

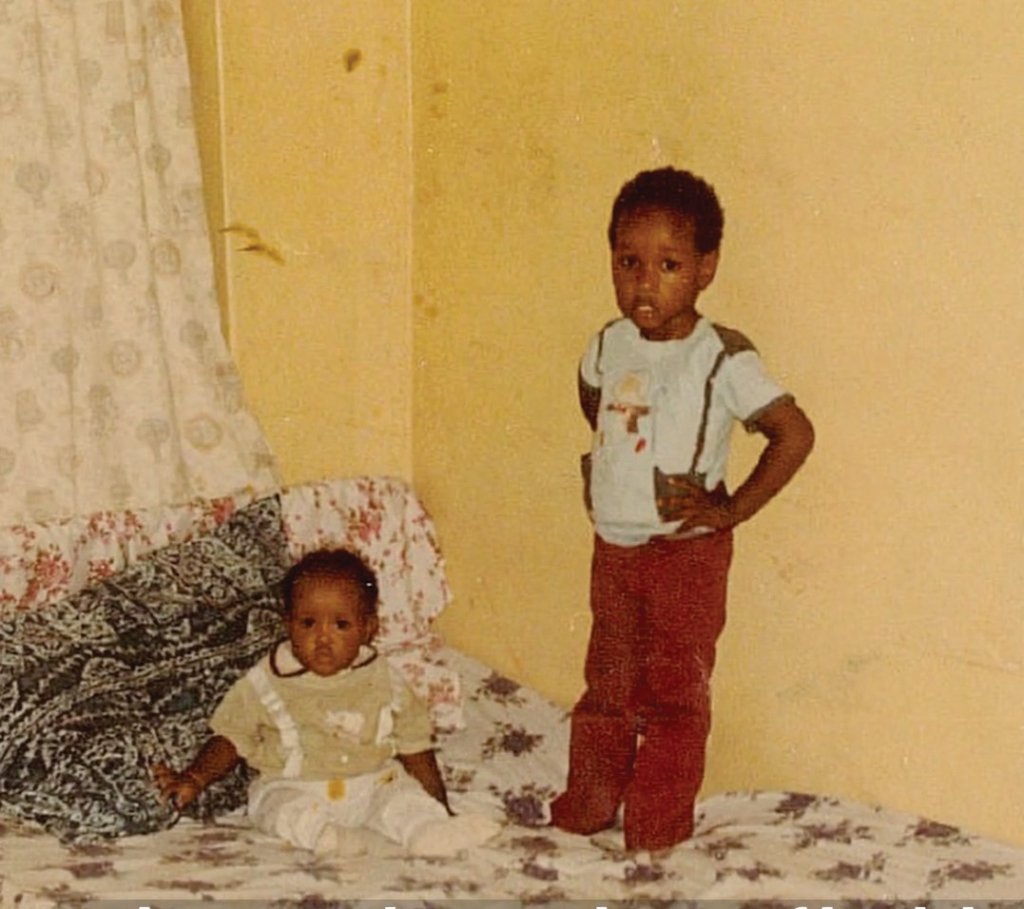

In 1993 the huge displacement of people caused by the war in Somalia, my home, coincided with the death of my father. And like that, I went through the difficult and traumatic experience of becoming both a refugee and an orphan. I was a nine year old boy, just arrived in a strange, new country, alone, having just helped to bury his father. I didn’t understand the language or the culture. Every day was a challenge to just make sense of the senseless.

I survived. But the way that that we understand survival in society is invariably that it is about the strongest surviving, but I think that that’s wrong. You need people to be able to share your pain. People who can understand your traumas, can empathise with your difficulties, who can help you overcome your shortcomings

I may have come through an incredibly difficult and traumatic period, but there are so many others who start out in similar circumstances, who may never get the chance to genuinely test their abilities, to genuinely push themselves, to genuinely make a success of themselves… to survive

"The problem that we face today is not a problem that came about overnight. So why do you feel that the answers and solutions have to be overnight?"

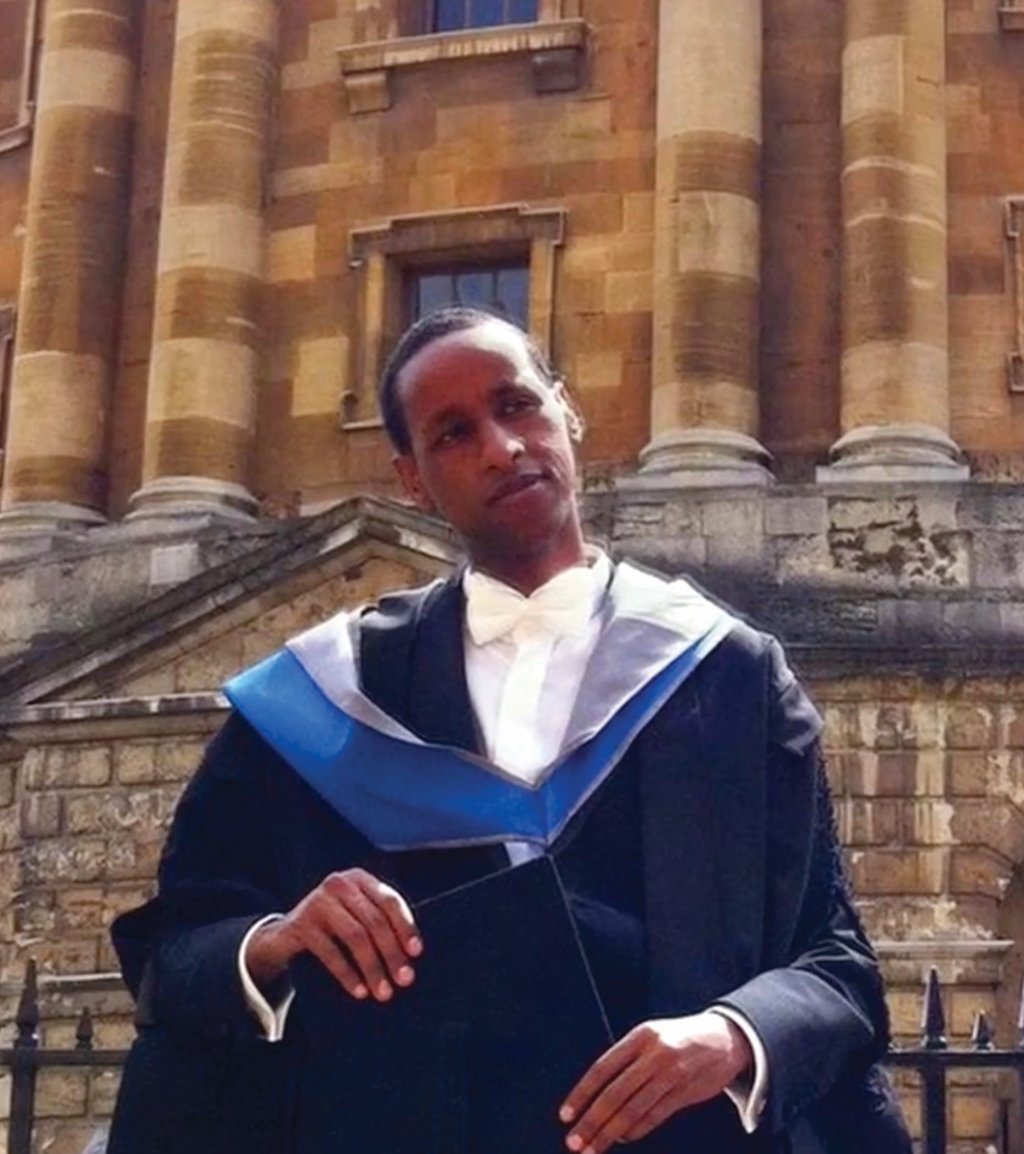

So much more than your hard work is required to succeed in modern societies, I have worked extremely hard – I continue to work extremely hard – but it would be remiss of me to simply suggest that because of my hard work, everything else follows. Luck is a huge part of the journey; telling young people, in particular, that the only thing that matters in society is your hard work is a very dangerous approach. There are other factors at play, including societal, or cultural contexts.

The consequences of understating this is that a young person who works extremely hard to no avail, will inevitably then conclude that no matter how hard they work, nothing will happen for them. But that’s because they’ve not understood that working hard simply gets you to the starting line. What matters are the lucky breaks, the people who mentor you. It’s that chance encounter with somebody who knows somebody who picks up the phone in your support.

Organisations need to work harder, too. Equity and inclusion is absolutely critical to the resilience of any organisation and, in order for you to survive, you need to be relevant, and to be relevant you need to be inclusive. Many organisations still approach D&I as a tick-box exercise and a lot of organisations struggle because they’re not willing to be patient. The problem that we face today is not a problem that came about overnight. So why do you feel that the answers and the solutions have to be overnight? Developing a truly representative team takes time.

The culture of an organisation can make all the difference when it comes to whether people feel like they belong, and that has to come from the leadership. Leadership has to be able to say this is a place where anyone from any background, from any place, if they’re good enough, are prepared to work hard, are willing to learn and open minded – this is a place for you to flourish. If that culture is wrong, everything else falls apart.

Society benefits from change, from disruptors who try and tell us look, this isn’t working, here’s how we might do something differently. Now, those disruptors may not succeed, they may not succeed at the first attempt, or the second or third, but we need disruptors to encourage us to think about problems in a different way. Because without the disruptors, we fall into that trap of groupthink, and we become resistant to change.