The Government’s new plan for growth picks up where previous Conservative strategies left off. That may not be a bad thing.

It wasn’t exactly remarkable. As he held on in his Surrey constituency in the early hours of 5th July, Jeremy Hunt went out of his way to offer platitudes about his successor. Rachel Reeves and Keir Starmer were, the outgoing Chancellor said, “decent people”, “committed public servants” who had changed their party for the better. The whole country needed them to succeed, he added.

But for those who had watched Hunt for some time, perhaps there was something more to it. In conversations, Hunt was said to have noted continuities between Labour’s plans for the economy and his own industrial policy (set out in the Advanced Manufacturing Plan), and to have stressed this was positive for the UK. His election night speech – coming as it did not long before the markets opened - seemed to underscore that point as Reeves headed to No 11.

Invest 2035: a flagship with foundations

Whether that was really Hunt’s intention is one for the memoirs. But this week, Reeves and Jonathan Reynolds appeared to pay him back with their new Industrial Strategy. Invest 2035 may decry the policy merry-go-round of recent years, but it picks up where the AMP left off. There is the promise of a dedicated sector plan for advanced manufacturing itself. The two strategies emphasise the role UK R&D plays in underpinning growth sectors across the board. Both documents embrace the importance of Government crowding in private investment to unlock industrial growth.

In areas where you would expect a change in Government to mean a big change of approach, the two strategies echo each other. Both talk up more effective regulation in unlocking growth, even if Invest 2035 leans more towards reform rather than removal. The AMP insisted the UK would not be drawn into a distortive battle over subsidies. Labour’s new offering is almost entirely silent on the question of subsidy control, bar one reference to in the context of competition policy. To those who listened to Treasury Chief Secretary Darren Jones before the election – during which he rejected the idea of a British Inflation Reduction Act with ‘lots of zeros’ after it – that is no surprise.

And then there are the Government’s reforms of inward investment structures, announced on the eve of this week’s investment summit. Here the new Government dropped almost all pretence of adopting a new approach, finally making good on recommendations Lord Harrington made to Hunt and Rishi Sunak for a beefed-up Office for Investment and new investor support services focused on planning and skills.

Ministerial engagement: call it a gift

So businesses get some stability from Labour’s new package, even if new ministers might not like to acknowledge why. What else do they get in with the bargain?

At first glance, not that much. At this stage of development, Invest 2035 kicks the funding conversation down the road. The strategy makes great play of Government needing to choose “what not to do”, before listing a grab-bag of sectors that are so broad they could include every bit of the economy. The decision to implement Harrington’s reforms is welcome, but as The Economist observes, it’s not clear whether new Investment Minister Baroness Gustafsson will have the power to co-ordinate the financial and non-financial inducements businesses are after.

The strategy’s broad-brush approach is hardly surprising. Those we have spoken to around Labour note the party struggled to translate the first version of this strategy produced in Opposition into what we’ve seen this week, with those working on the policy handing it over to civil servants who got little time or guidance to develop it given the limited access talks before the election. The Government essentially acknowledged this with a long period of consultation and more nice words about working in partnership with industry.

But there is one goodie under the tree. With every Conservative administration, at least one of the top ministries resisted a whole-of-government approach to industrial policy. This was especially the case when Sunak was Chancellor and PM. As Giles Wilkes has noted, Invest 2035 immediately has a leg-up on its predecessors in that the Chancellor gave it her public seal of approval. There is also a role for Deputy PM Angela Rayner in ensuring the OFI’s planning services deliver - businesses should pay close attention to the involvement of such a senior political figure in ensuring the Government’s new approach to FDI delivers.

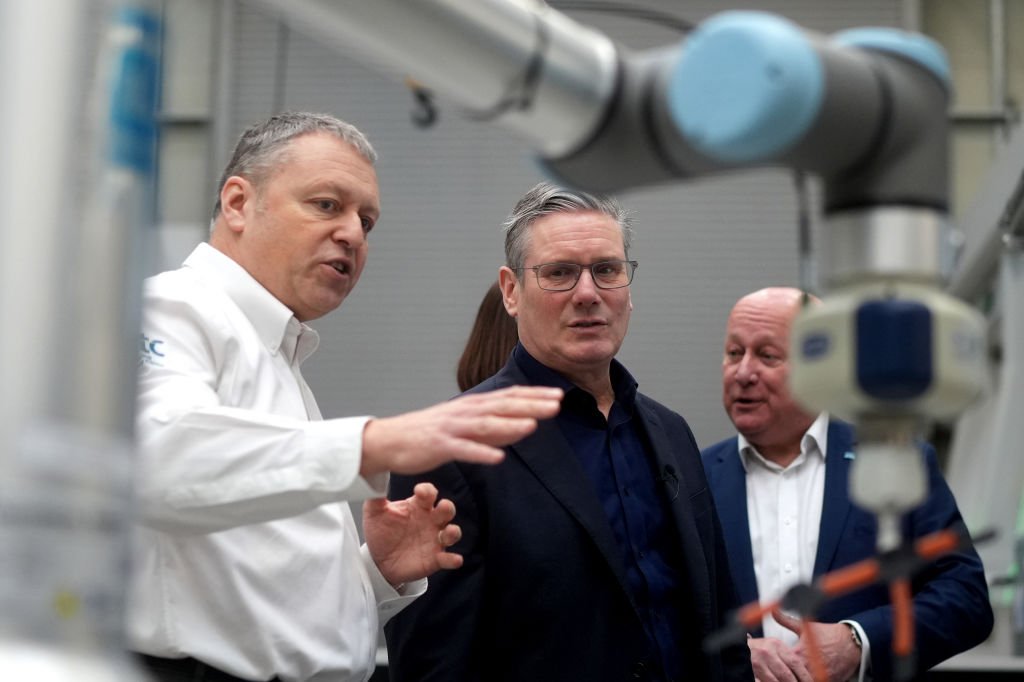

And then there is Starmer himself. One veteran watcher of the PM wondered if he would do ‘Macron-style text diplomacy’ after hobnobbing with so many executives at Guildhall. It’s hard to envisage the man once thought to be the inspiration for Mark Darcy suddenly finding his inner Daniel Cleaver, but he is trying. The PM moved quickly to try and contain the row with DP World as P&O’s Gulf backers threatened to exit the summit, facing accusations of throwing his Transport Secretary under the bus in the process. In his Economist interview, he also insisted it would be as much him as Gustafsson on the hook for delivering the incentives firms wanted to see. Whether or not he delivers will determine whether businesses were right to place their faith in him.