When the late Alistair Darling got up to deliver the last Labour Budget more than 14 years ago, the economic backdrop was the fallout from the one of the worst financial crises in British history and the political future for his party was a grimly inevitable general election defeat and more than a decade in the wilderness.

The task facing Rachel Reeves today wasn’t quite as hard – but it wasn’t far off.

The UK’s first female Chancellor had somehow to create a narrative which combined hope for the future with the inevitability of huge tax rises, balancing growth-driven investment in public services and a prudent stewardship of the nation’s finances.

She went at least some way to achieving her goal. But circumstances dictated that the overall mood of Labour’s first Budget was a far cry from the hopeful vision of the future that all new incoming governments would wish to project. There was need, above all, for realism.

Tony Blair’s sunlit uplands were flattened by a combination of a £40billion tax ‘bombshell’ – the biggest in history - and a grim five-year forecast of sluggish growth (the central ‘mission’, remember).

However, a tweak to the government’s fiscal rules allowed the Chancellor the ‘headroom’ to announce around £100billion of extra capital spending over five years (using the ‘investment’ formula beloved of Gordon Brown) – including on health, transport, homes, and schools.

The biggest chunk of money is set to flow to the NHS, with £22.6billion on day-to-day spending and £3.1billion on capital spending both this year and next.

In what was a nakedly political Budget, the Chancellor once more channelled her political hero Gordon Brown (as a student, her friends presented her with a framed photo of him) by challenging the Tories to oppose the new spending and blaming them for bequeathing her a £22billion black hole.

The roadmap for Labour’s drive to win the next election emerged clearly: with a renewed focus on ‘working people,’ a definition of whom had tied her colleagues in knots for days. To the surprise of some, Reeves kept the temporary fuel duty cut introduced under the Conservatives and ruled out an inflation-linked increase. In another unexpected move, coming close to the status of a ‘rabbit,’ she did not freeze income tax thresholds but allowed them to rise, freeing millions from being dragged into higher tax brackets. There was even a symbolic 1p cut in the price of a pint.

Employers shoulder the tax burden

A series of targeted tax increases provided the counterpoint. You almost thought the Chancellor would do a reverse Neil Kinnock from 1983: “I warn you not to be a second homeowner, I warn you not to be a non-dom, I warn you not to be a tenant farmer, I warn you not to travel by private jet or send your children to private schools.” It was a rapid admission that at least part of the coalition that helped win Labour such a massive majority less than four months ago was unlikely to survive beyond the Budget.

The biggest chunk of the £40 billion tax hike was – as expected – a massive rise in employers’ national insurance (NI) contributions, bringing in £25billion. The rate went up from 13.8 per cent to 15 per cent but the most painful part was halving the salary threshold at which employers start to pay, from £10,000 to £5,000.

In crude terms, for a person on a salary of £30,000, employers will be paying NI an additional £866, or 2.9 per cent annually, on their salaries – effectively a 3 per cent ‘pay rise’ that will go to the Treasury rather than the employee.

Growth forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) saw the measure rising from 1.1per cent this year to 2.0 per cent next, but then limping along to end up at 1.6 per cent in 2029, the likeliest date of the next general election.

One result of this is that household disposable income – another key factor that will decide Labour’s fate at the ballot box – is forecast to drop between 2025 and 2028 as a direct result of the measures in the Budget before recovering. Mortgage rates are predicted by the OBR to rise by up to 1 per cent by 2030.

The Chancellor made positive noises about efficiencies in the public sector, which will please the business audience, as well as emphasising the important role played by tech in helping drive reforms.

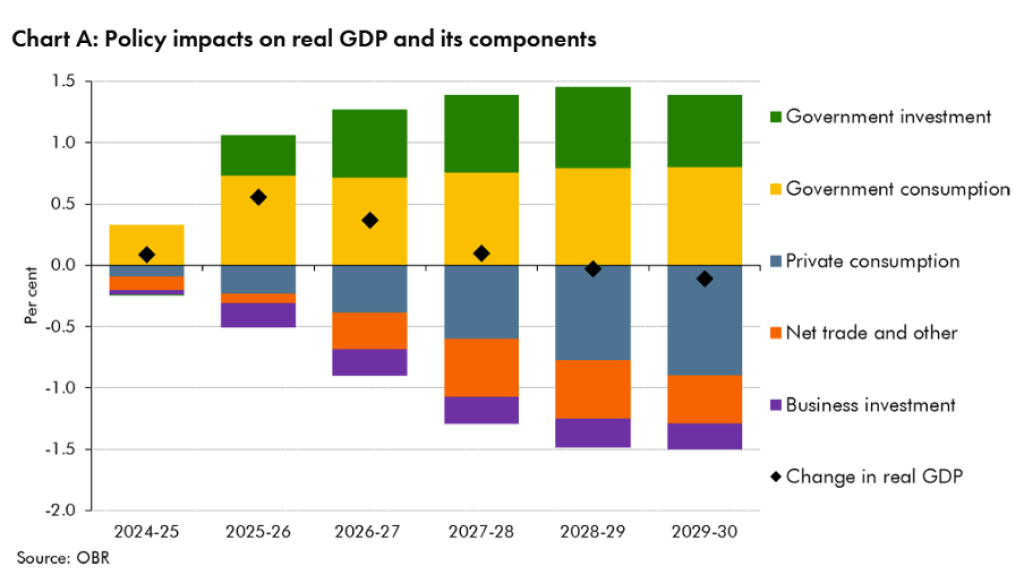

However, the OBR’s own forecasts on the policy impacts of the Budget on growth all suggest a strong negative impact on both private consumption and business investment – with the only real net contribution to growth coming from government spending.

Market reaction, broadly neutral as Reeves was speaking, began to turn less favourable in the following hours, with the cost of government borrowing edging up.

Reeves and Keir Starmer, who are certain to face further high wage rise demands in the public sector, must continue to tread a wary path through the business community for years to come. They must also to show voters they are doing more to protect living standards and improving public services to protect their majority in five years’ time.